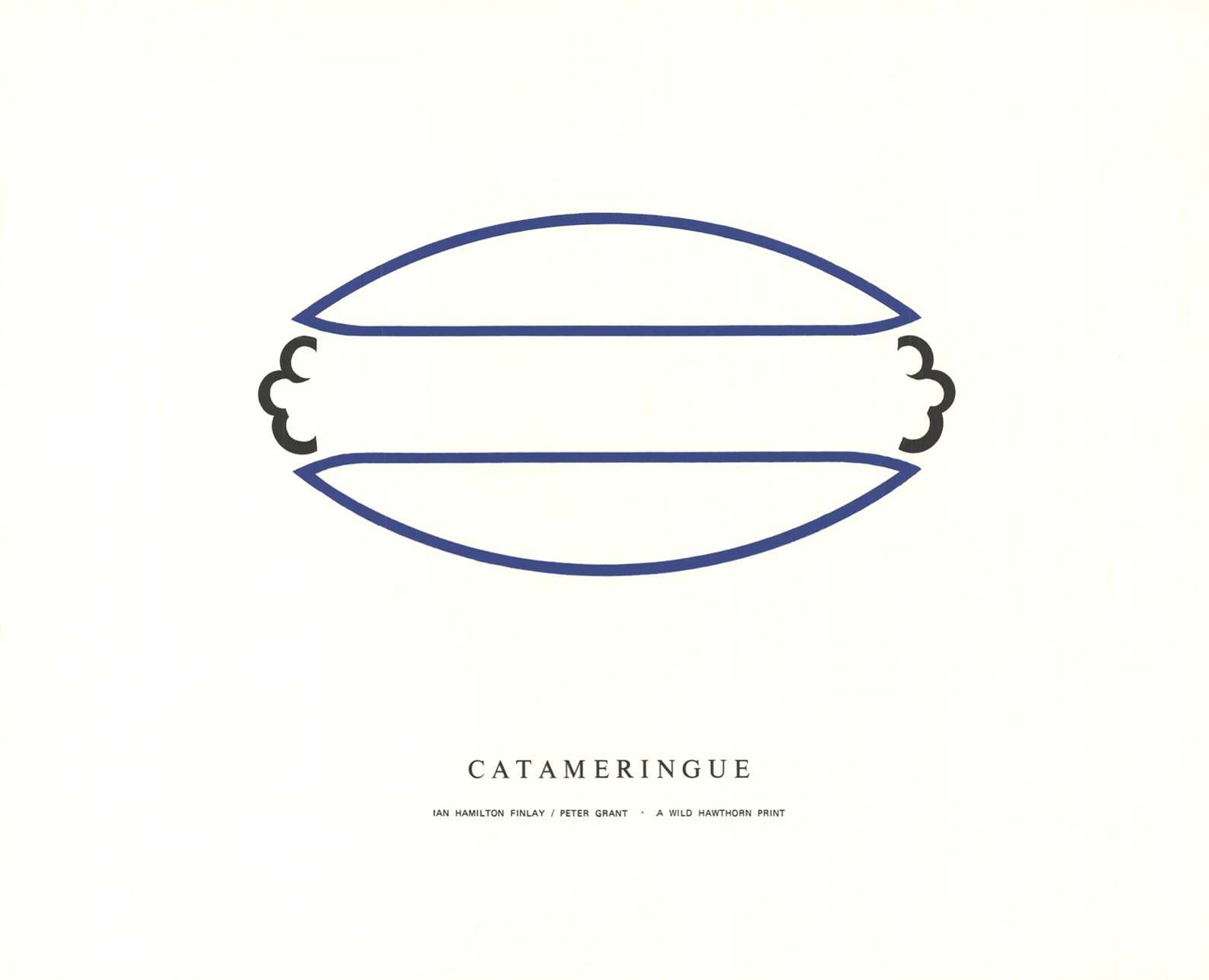

After Catameringue

I’m most familiar with this silkscreen from seeing it at the Edinburgh home of the photographer Robin Gillanders, where till recently it hung in the hallway of his and his wife Marjory’s New Town flat. It’s one of a number of prints they were given by the Scottish poet, artist, gardener, revolutionary, philosopher… Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006). He and Gillanders began collaborating in 1993, and as with many such successful interweavings of ideas and skills, a close friendship soon developed.

Catameringue, produced in collaboration with Peter Grant (typesetter in 1968 of Sea-poppy 2), was published in 1970 by Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn Press. It is delightful, and amusing, but while I have always enjoyed the qualities that link it with Finlay’s oeuvre more generally (boat/ sea, concision, wit, collaboration, text/ art, its status as a poster-poem, the sophistication of the design), I've never really given it much thought. In general, beyond the initial, pleasurable intrigue – a hallmark of his production, like the feeling of recognition (whoever the collaborator) – the work that Finlay creates is so loaded with implication, and so condensed, that coming to terms with it requires time and effort. Being classical, it was, he insisted, always finally amenable to rational explanation, and certainly not to be explained biographically. He once remarked to the collector Ronnie Duncan concerning a possible sundial commission – a very different beast admittedly – that “any projected work will not be a matter of what people call ‘visual impact’ (horrid phrase) but will have a slow excitement, a kind of seep (as it were) of meaning, and not a sudden wham.”[1]

As for Catameringue (and leaving aside thoughts of slapstick comedy) even if it does provide more of an initial “wham”, the possibility of “slow excitement” remains. It doesn't take much familiarity with Finlay's output to appreciate the potential he found in the medium of printmaking, as he did in the many others he employed. As ever, the print is precisely conceived and realised, from the minimal symmetry of the meringue/ hull shapes, in what looks like navy blue, to the stylised puffs representing whipped cream/ aquatic wash, and from the careful placing of the texts, including the clinching pun, to the typeface and script. Considered in its guise as a catamaran, the “puffs” rather oddly appear at both bow and stern, which seem to be interchangeable – but of course it is also a meringue.

Lightness of some kind, wit, humour, the exhilaration of beauty and harmony, of extraordinary improbability, characterises many of even Finlay’s most challenging productions, but in this case, beyond the art – no small consideration – is it meringue-y lightness alone? Or do the puffs suggest the volutes of Corinthian capitals, anticipating the poet’s later polemical interest in neoclassicism? Unlikely, but given Finlay’s engagement with that subject – and, as the critic Yves Abrioux wrote in 1985 – with “the ‘neoclassical rearmament’ which [was by then] Finlay’s major preoccupation, and which [was] a vigorous response to the contemporary cultural context”, as well as with conflict more generally, and with warfare and weaponry, it is curious to note that Catameringue is to be found in the collection of the Imperial War Museums.[3]

So too are three other works by Finlay that seem rather less of a surprise in that context: Necktank, Arcadia, and Proposal for the Camouflaging of a Type 22 Pillbox in a Classical Park.[4] One might wonder whether like the “pineapples” in Finlay’s Hypothetical Gateway to an Academy of Mars, at Little Sparta, a “catameringue” really is a weapon of some kind... ([Update 17/5/25] The pineapples take the form of hand grenades. Commenting in Fragments, published to accompany this year's centenary series of exhibitions of Finlay's work, the writer Prudence Carlson, referring to Five Finials, remarks on the fact that "grenade" is "a now obsolete term for the pomegranate fruit.") [5] Yet the museum’s “Object Description” suggests otherwise:

two blue ellipses joined by two black shapes, which combine to create the impression of a cream filled meringue. It also suggests the shape of a catamaran seen from below, with the title a play on words.

But I saw another copy recently, at the Pier Arts Centre, in Stromness, Orkney, my local – if rather more than local – gallery. Catameringue is one of five Finlay prints it was presented with some years ago by the Contemporary Art Society. All came originally from the collection of David and Liza Brown, along with Acrobats (1966), Sea/ Land (1967), Homage to "Mozart" (1970) and Homage to Malevich (1974).[6]

These and the five others that comprise the Pier's holding of Finlay's prints are on display until early June this year, the larger part of a modest but satisfying centenary gathering of Finlay’s work. As well as the poet’s important early links to the islands, its Ian Hamilton Finlay and Orkney aims to illustrate aspects of the development of what the gallery terms his “deeply radical ideas about the place of art in society”. This is achieved through the display of a selection of correspondence it also holds: not so much as concerns the "neoclassical rearmament", but rather, in this case (what was one of its main provocations) "The Fulcrum Affair", of 1969-1974. Finlay's campaign to have a work of his properly described as a third, and not a first edition, concerned The Dancers Inherit the Party, a collection of lyric poems. This was partly composed in Orkney, when Finlay spent a few months living and working there in 1959, and it was published the following year, by Migrant Press, a small but influential transatlantic imprint.

I wondered idly what I might say about the prints, for I am to speak there sometime on an aspect of my research on Finlay’s early career. In particular I began to think about Catameringue, not because I’d choose it as a subject, but from curiosity, and partly because at the opening I saw someone look across, momentarily perplexed, then catch on – “catameringue!” – and grin delightedly.

The other work the Pier has on show is Robin Gillanders’ fine large-format photograph of the poet’s 2005 installation on the island of Rousay: Gods of the Earth/ Gods of the Sea, commissioned by the Pier Arts Centre (as was the photograph) and created in collaboration with Pia Maria Simig and Nicholas Sloan. I know well enough what I might say in this case, based on an account that I contributed to a book he brought out last year. In Ian Hamilton Finlay: Little Sparta and Collaborations, Gillanders surveys the outcome of “an extremely fruitful … collaboration and close friendship” that continued over thirteen years, and in a substantial sense, beyond that.[7] I've recently revised the essay for publication in a booklet, and may also publish part of it here.

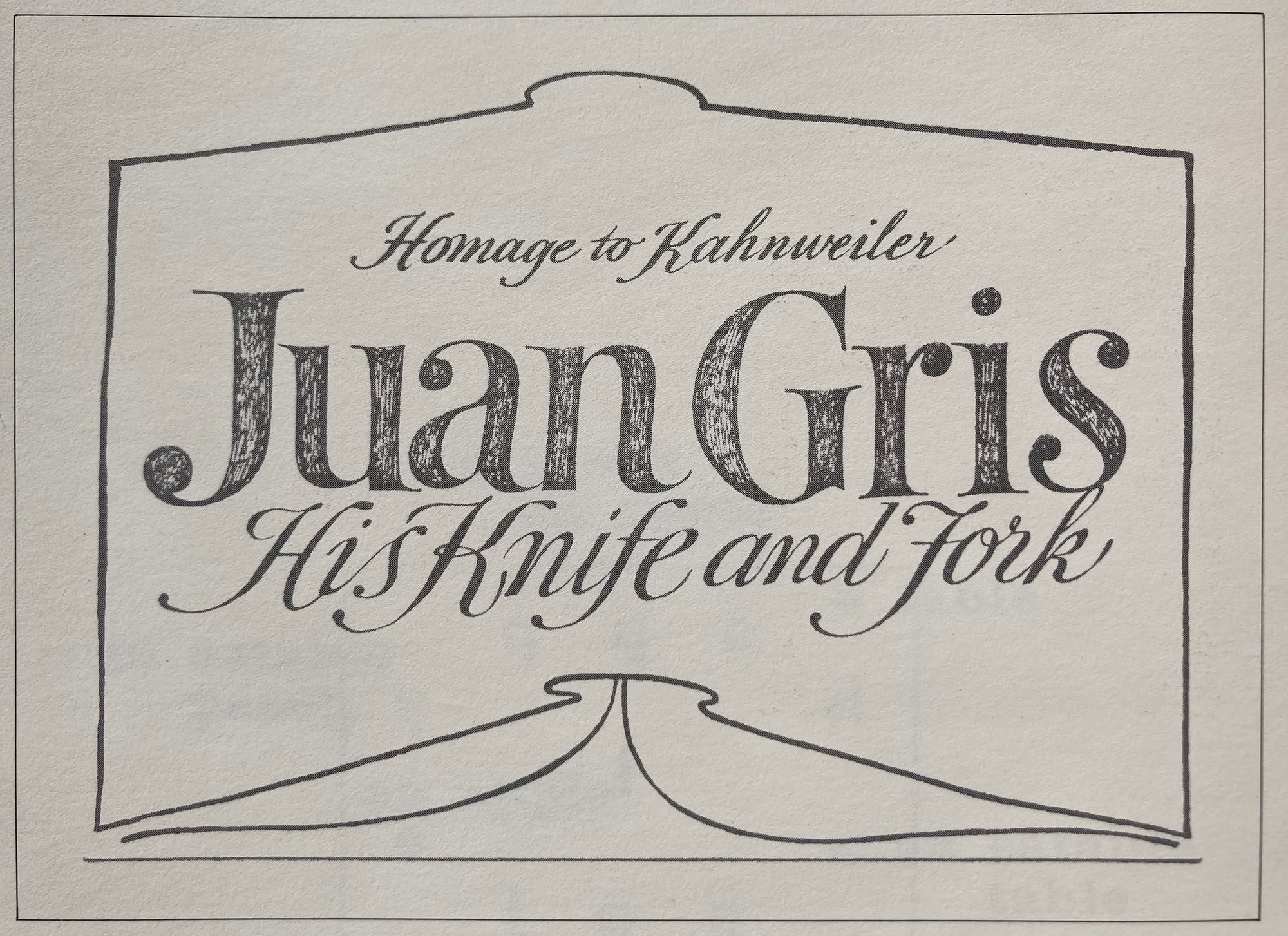

As regards “here”, and the present article (or its first installment), I’m writing it really to try out the platform, to find a home for a number of bits and pieces accumulated over a decade and more of research, which in the background is slowly becoming a book, on Finlay’s life and work. His “Knife and Fork”, as he riffed in a postcard of 1972, a homage to the Jewish-German collector, dealer and art historian Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979).

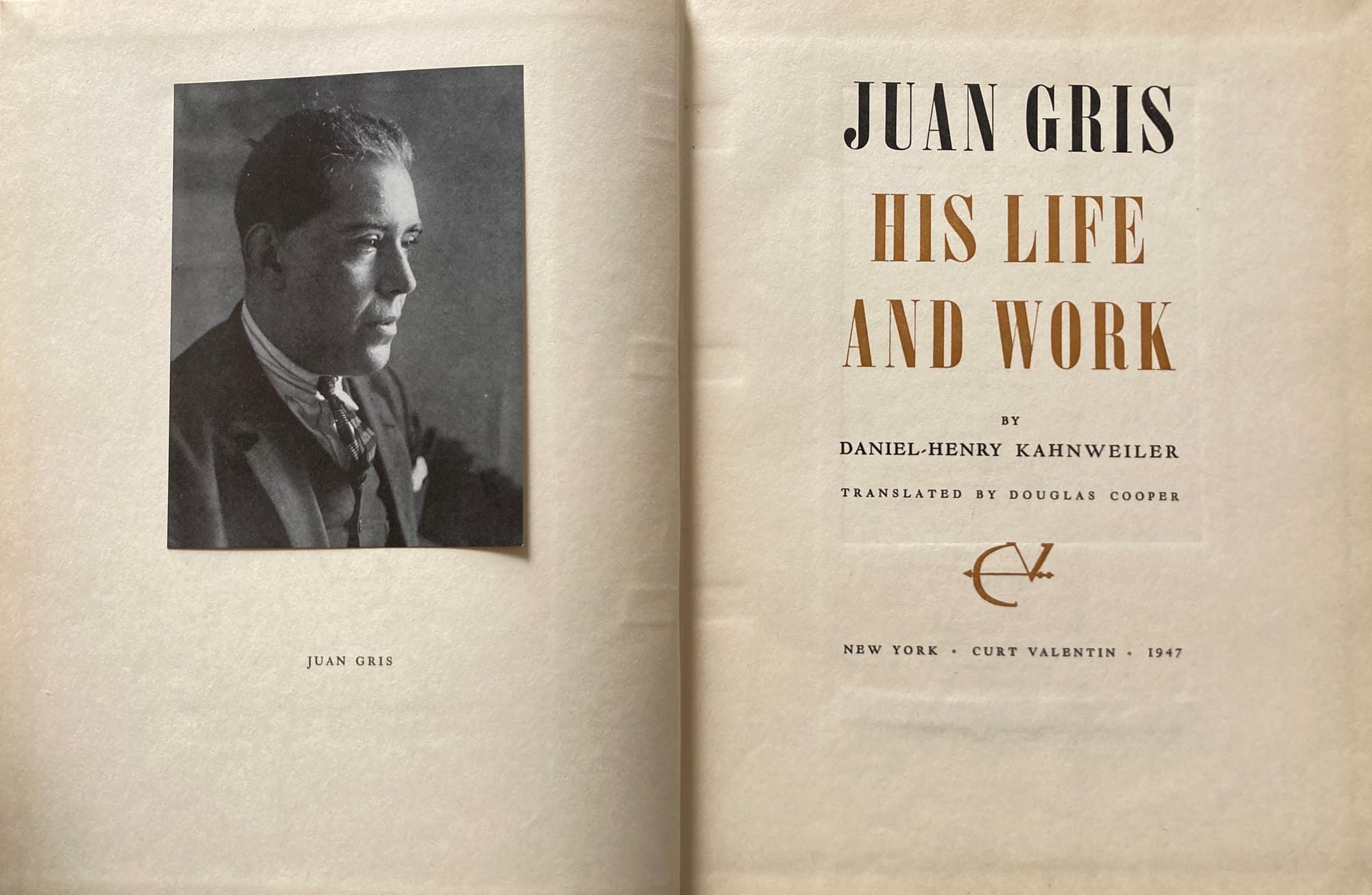

He was referring to the title of Kahnweiler’s book about Juan Gris, perhaps in reference to a painting such as Fruit-dish and Water-bottle (1914).[8] Juan Gris: His Life and Work came out in an English translation in 1947, but an earlier survey on Gris, also by Kahnweiler, published in Leipzig in 1929, though apparently not translated into English, as well as other material on the topic, may have been available to Finlay in his early youth, in Glasgow. This phase of his life is little known about in any detail, but among the few comments he made is that at that time he read “many books on cubism”.[9] The movement changed everything, of course, and it profoundly influenced Finlay, and Gris was his "favourite" cubist.

In 1965, at Gledfield Farmhouse, in the eastern highlands, Finlay began to take his work as a concrete poet from the page into three dimensions, and then into the landscape and into architectural environments. He and his partner Sue Finlay moved there from central Edinburgh in May that year, his chance to escape at least some of the constraints of penuriousness and agoraphobia, and to find a certain liberty in their new rural surroundings. Working with Dick Sheeler, he first created mural versions of a number of his early concrete poems, beginning with “To the Painter, Juan Gris” (also known as “Happy/ Apple”).

In a letter of 1970 to the Canadian poet and critic, Stephen Scobie, Finlay recalled that it was at Gledfield that he “re-read the Kahnweiler book carefully,” agreeing that it “was crying out for a concluding chapter on concrete poetry.”[10] His suggestion that Scobie himself should write that chapter was the basis for the book in which the reference appears.

Finlayan homages to Kahnweiler are numerous. An intriguing example occurs in his 1981 book, An Improved Classical Dictionary, in which one of the entries reads:

MANDOLIN, n. a painter’s instrument. Rather like rhymes in a poem, two forms, generally of different sizes, are repeated. In 1920 these metaphors are fairly evident and are based on the simplest objects (playing cards, glasses etc.). Then a bunch of grapes is compared to a mandolin. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Juan Gris. [11]

The paradox in Finlay’s terse definition is explained by the reference that succeeds it. This is taken – I can reveal – from page 100 of the 1947 volume.[12] There, the quotation used by Finlay is preceded by the sentence,

These [rhymes] were intended by Gris as plastic metaphors to reveal to the beholder certain hidden relationships, similarities between two apparently different objects.

And so here we are back at Catameringue, although for those who are familiar with the 1960 collection mentioned above, The Dancers Inherit the Party, the reference will also bring to mind another vessel, and another kind of food, similarly-shaped, but in taste-bud terms antipodal.

In one of the “Orkney Lyrics”, the "English Colonel explains an Orkney boat" as follows: “You see, it has a point at both /Ends, sir, somewhat /As lemons.”

By the time Catameringue appeared, ten years after that more traditional poetic phase (Finlay had previously, and quite successfully, worked his way through painting, prose and dramatic writing), and on the other side of his direct involvement in poesia concreta, the poet-artist was able, if he so chose, to dispense with more extended verbal comparisons. In 1970 too, he published “Still Life with Lemon”, one of a number of postcards that draw upon the same visual “rhyme”. The first of these was “3 Blue Lemons”, printed by Hamish Glen of The Salamander Press in 1968, the same year in which Finlay published the silkscreen Marine, with Patrick Caulfield, another variation on the theme, drawing also upon Caulfield's bold, pared-down printmaking style.

Homage to Kahnweiler was only one of six such postcard homages that Finlay published in 1972. The dedicatees of the others were E. A. Hornel, Georges Seurat, Jonathan Williams, Wassily Kandinsky and Walter Reekie’s Ring Netters. (Reekie was a Fife boatbuilder of the early-mid twentieth century, best known for his design and construction of that kind of craft. Finlay repeated the idea, with variations, in a postcard of 1996, another Olympic year, the cards also paying homage to the Games’ famous interlocking rings.)[13]

It was also in 1972 that, with Jim Nicholson, Finlay published the poem-print Homage to Modern Art, and with Ron Costley, Prinz Eugen: homage to gomringer. As Abrioux observed, with particular reference in this instance to his “series of militaristic homages to artists in the suprematist tradition” (including Malevich) “Ian Hamilton Finlay has long practised the epideictic mode of the homage”.[14]

Abrioux, to whom homage is also due, as it is to several other long-established, expertly committed writers and commentators on Finlay, is a name known to anyone seriously interested in his work. Others prominently include not least Finlay's son, the artist and poet Alec Finlay, as well as the doyen of Finlay criticism, Stephen Bann, who among numerous works of commentary and analysis – in many cases created in collaboration with Finlay – made a substantial contribution to Abrioux's A Visual Primer, still the standard text.

By comparison, one of many that might be made, and while I admire Finlay’s, and their rigorous concision, in this series I’ll be allowing myself a fair degree of discursive scope, as I have here too. Eventually, after a brief return to Orkney, I'll be meandering further through the Gillanders’ print collection, somewhat, someone suggested, in the manner of an interiors magazine. (A coincidental homage, as it turns out, to “Written on Tablets of Stonypath”, Alec Finlay’s article in the May number of The World of Interiors.)

Part II, “An Island On Your Doorstep”, should appear here in a fortnight or so.

[1] IHF, letter to Ronnie & Henriette Duncan, 20 January 1976. Finlay Papers, Getty Research Institute.

[2] https://krollermuller.nl/en/ian-hamilton-finlay-of-famous-arcady-ye-are

[3] Yves Abrioux, Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer (London: Reaktion, 1992) p. ix; https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/9260

[4] https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?filters[makerString][Finlay%2C Ian Hamilton]=on

[5] Pia Maria Simig (ed.) Fragments: Ian Hamilton Finlay ([Melton Woodbridge]:ACC Art Books, 2025), n.p.

[6] https://contemporaryartsociety.org/search-results?index=object&search_word=&sort=relevancedesc&conditions[]=field_related_museums=935&page=1

[7] Robin Gillanders, Ian Hamilton Finlay: Little Sparta and Collaborations (Edinburgh: Studies in Photography, 2024).

[8] In the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, Holland. Cf. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Juan_Gris,_1914,_Le_Compotier_(The_Fruit_Bowl),_chalk_and_oil_on_canvas,_92_x_65_cm,_Kröller-Müller_Museum,_Otterlo,_Netherlands.jpg

[9] https://archive.org/details/juangrishislifew0000kahn/mode/2up; https://archive.org/details/juangris00kahn/page/16/mode/2up Abrioux (1992) p. 1.

[10] Stephen Scobie, Earthquakes and Explorations: Language and Painting from Cubism to Concrete Poetry (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), p. xii.

[11] Parrett Press, Christmas 1981.

[12] Cf. https://www.ukposters.co.uk/art-photo/the-mandolin-la-mandoline-1921-v89746

[13] https://emuseum.aberdeencity.gov.uk/objects/119713/homage-to-walter-reekies-ring-netters; https://emuseum.aberdeencity.gov.uk/objects/118852/homage-to-walter-reekies-ring-netters

[14] See e.g. “Analytical Cubist Portrait/ Daniel Henry Snowman”, in The Mailed Pinkie, with Gary Hincks (Alsbach: Verlaggalerie Leaman, 1982), n.p.