After Catameringue II – "An Island On Your Doorstep"

The Pier Arts Centre's Ian Hamilton Finlay and Orkney runs in tandem with the gallery's main exhibition of the season, Bet Low: An Island On Your Doorstep. The subtitle for the latter was selected from a passage in the artist's own writings about Orkney, where the primary reference is to the view, as above, from her own small cottage at Mill Bay, Hoy.

Like the Finlay show, An Island On Your Doorstep is a centenary event, arranged in collaboration with the Reid Gallery at Glasgow School of Art. [1] Low trained as a painter at GSA between 1942-45, and Finlay too attended the School, slightly earlier (though younger by a year) and more briefly. The two knew one another at that time, both of them exhibiting in a group show in 1950, and they remained in contact, intermittently at least. Unlike Margot Sandeman, another GSA contemporary, Low never worked collaboratively with Finlay. An approach was made in the earliest days of the Wild Hawthorn Press – in 1961 – but for reasons to be considered elsewhere it did not work out.

Originally from Gourock, Low remained in Glasgow following her Diploma year, and in 1947 she married the painter Tom MacDonald (1914-85), also from the city, and also with a firm commitment to the political left, with whom she had a son and a daughter. As well as devoting herself to her own work, she made important and lasting interventions in the city's art scene.

Finlay's origins are a rather more ambiguous matter, as touched upon briefly again below, though there's no doubt historically that while brought up in Scotland, partly in Glasgow, he was born in Nassau, Bahamas.[2] He too got married in 1947, to an artist from Glasgow named Marion Fletcher, but by contrast with Low and MacDonald, the couple moved away from the city, first to Perthshire, where in the mid-50s they separated (there were no children), later getting a divorce. Finlay himself moved to Edinburgh, and then in 1966, after spending a year at a farmhouse in what was at that time Easter Ross, and following a few months in rural East Fife, he and his partner Sue Finlay took up residence with their infant son at Stonypath, Dunsyre. From there, he too intervened in the cultural scene, to rather different effect.

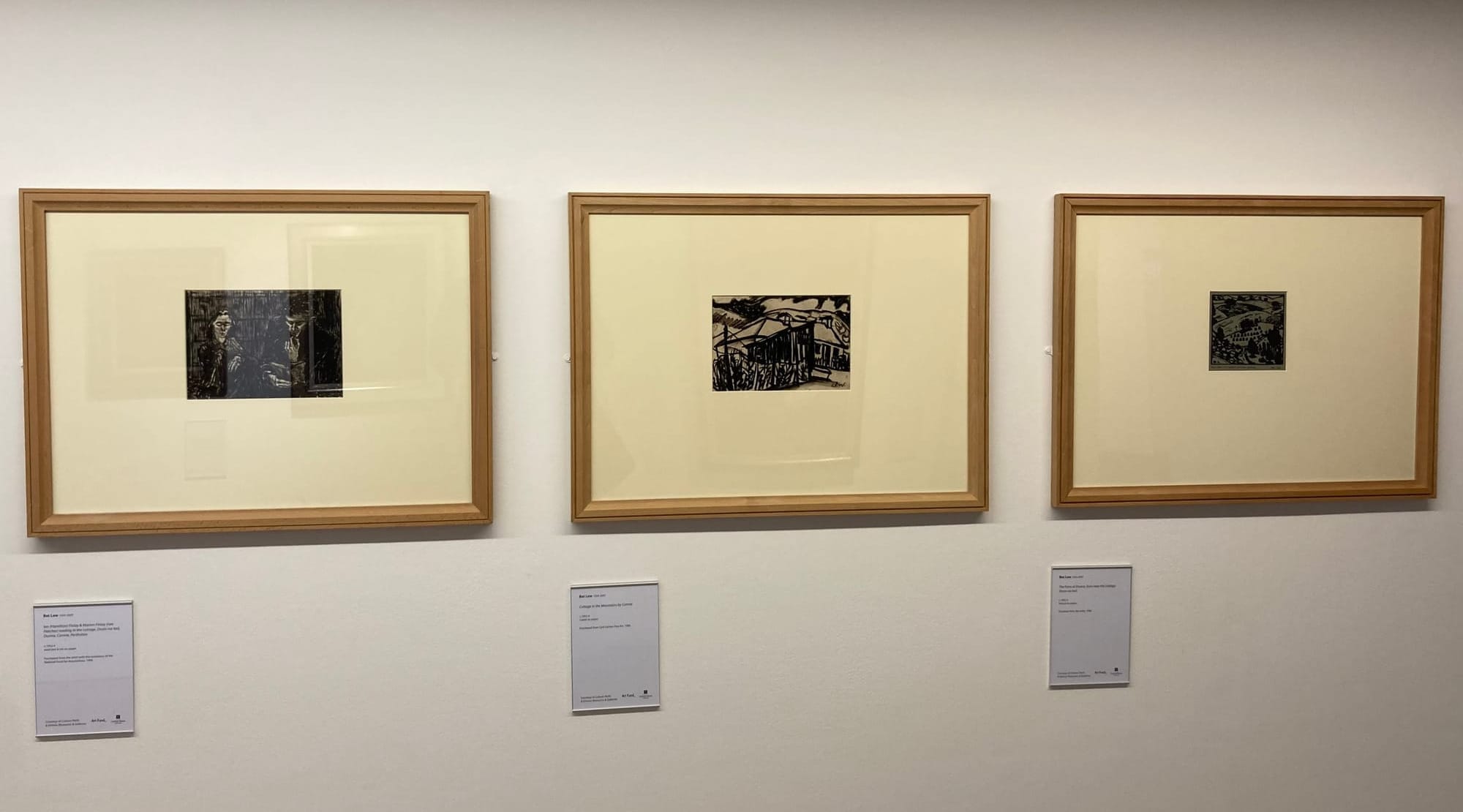

The archival record is at best patchy, but a sense of the two artists' continuing friendship, and of the esteem in which Low held Finlay, is evident in a selection of her manuscripts included in the exhibition of her work. The connection is also conveyed in her c. 1950s companionably informal drawing of Finlay and Marion and in two others of their Perthshire cottage at Dunira near Comrie.

Bet Low, Ian Hamilton Finlay & Marion Finlay (nee Fletcher) reading in the cottage, Drum-na-keil, Dunira, Comrie, Perthshire. Courtesy of the Bet Low Trust and Perth Art Gallery.

Installation view at the Pier Arts Centre, with thanks.

The concurrence of the two exhibitions in Stromness draws attention to the early link between their careers, but it also acknowledges the fact that both artists later formed an important connection with the islands. Separately, and at different times, each was attracted to the rural, maritime north (and in Low's case also west) of Scotland, as an alternative to, or change from the city, its life, or the subject matter available there.

If the exhibitions seem a little out of kilter in terms of their scale, it is nevertheless the case that Finlay’s own centenary is to be marked at numerous galleries throughout Britain and Europe. The Pier's show was the first such event to take place this year, the next one to open having been Ian Hamilton Finlay, at the National Gallery of Scotland's Modern Two. As well as presenting a range of Finlay's works, both galleries take care to highlight such integral considerations, as the Pier puts it, as Finlay's “deeply radical ideas about the place of art in society”.[3]

Successful as these exhibitions have undoubtedly been, benefitting greatly in each case from the curatorial expertise brought to bear, perhaps unsurprisingly the main impetus around the Finlay centenary has come from his Estate, and its far-sighted Executor Pia Maria Simig. Collectively entitled Fragments, it is a remarkable endeavour that takes place on a scale that is both attention-grabbing and pleasingly reflective of the artist's established international significance.

Ingleby in Edinburgh is one of eight prestigious private galleries at which exhibitions of work from Finlay's later period are now taking place, with concomitant shows in London, New York, Brescia, Hamburg, Mallorca, Vienna, and Basel. Further information may be found on the Ingleby website, where a feast of information and imagery is available – including as regards the substantial publication that Simig has edited – as well as on those of the other participating galleries. [4]

One feels that Low would be only too delighted at the attention that is being paid to Finlay's work in those quarters – as he would surely welcome the initiatives taking place on her behalf – and by turns welcoming and disparaging of the range of responses it has attracted in the press. With Magnus Linklater, Chairman of the Little Sparta Trust, we can imagine what Finlay's response might be. Introducing his recent article in The Times, in response to "the scabrous attack mounted against the Scottish artist Ian Hamilton Finlay in The Guardian", he remarks that "since the famously combative Finlay is no longer around to do it himself, I will happily take up the mantle", and having done so, rightly demands satisfaction. [5]

In part with such considerations in mind, and beyond the very welcome centenary events, including talks and publications, there is surely further work to be done. According to the Reid Gallery, Bet Low: An Island On Your Doorstep "celebrating the centenary of her birth will reflect on Bet Low’s working life, from early studies of Glasgow to the late Orkney landscapes and go some way in reassessing this important Scottish artist’s contribution to Scottish art and culture." [6]

It would be welcome indeed if one or another of our national cultural institutions felt it was not too soon to embark on a similar programme in respect of Ian Hamilton Finlay. (Which might also have the effect of encouraging a more robust basis for critical discussion.) Like others I regretted that the Modern Two exhibition did not take place during the summer months, when Little Sparta is open to visitors, but while I thoroughly enjoyed its display of its Finlay holdings – and as ever the gallery's permanent Finlay installations in its grounds – I couldn't help being struck by the coincidence of his Nature Over Again After Poussin being installed – for the duration of the exhibition – in the same area of the gallery (though walled-off) as their permanent display of the workroom of the Scottish artist and sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, popular and highly regarded as that surely is.

I've added my tuppenceworth elsewhere to the many appreciations that have been written of this major work by Finlay – Sue, Dave Paterson and Wilma Paterson being the principal collaborators. Transporting, captivating, wittily alert to all the implications it might evoke, it rewards more and more repeated viewing. No less certainly than with Paolozzi's studio (which is likewise provided with a viewing "platform"), one wants to become forgetfully immersed in its details and vistas, though very far from getting lost: rather like the experience of the garden, if the overall comparison can be understood as intended. As much as anything else that the work succeeds in achieving, it epitomises the imaginative force of the project that a decade or so before its realisation, Finlay and Sue undertook in transforming their hillside and moorland at Stonypath.

In addition to the matter of the work's own qualities, both individual and exemplary, a comment by the historian Patrick Eyres will be of interest as regards other matters under discussion. Eyres writes that "[t]he celebrated garden created around [Finlay's] home at Little Sparta in southern Scotland was nurtured both as an artwork-in-progress and a nursery of ideas which became transplanted into gardens, parks and cityscapes across Britain, mainland Europe, and the USA."[7]

It would be a fine thing if there were a space somewhere in the land to display this work on even an occasional longer-term basis, as a complement to or intensification of the experience of visiting the garden, and as an orientation towards important aspects of its history.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Nature Over Again After Poussin National Galleries of Scotland. Permission pending.

But to return to landscapes and landscape representations of the kind with which we began, it is fair to say that – perhaps paralleling the appreciative wonderment of those seeing some rarely exhibited Finlay items in the Modern Two display – Low’s work at the Pier Arts Centre was greeted by visitors as something of a revelation in the recent history of the depiction of the islands. (Her last exhibition there took place in 1986.) It certainly merits the exposure, in Orkney, as elsewhere, and one hopes the Reid Gallery's ambitions are fulfilled.

As to her connection with the islands, in 1967 she and MacDonald bought a small holiday home in Hoy, near the village of Lyness, and returned there summer after summer (in some respects this bears comparison with the quite different kind of relationship with the island that the composer Peter Maxwell Davies famously began some years later).

One of many buildings left over from the huge influx of service personnel during the war, the Low/ MacDonald property was inexpensive enough to buy “sight unseen”. As another GSA contemporary, the art critic Cordelia Oliver, noted of Low in 1985, the decision “led to striking developments in her work.”[8]

Her “whole career [was] devoted to exploration and discovery”, Oliver wrote, and the Pier show provides rich insights into its progress from early expressionism by stages to a culmination in abstract treatments of landscape subjects.[9] Many of these really were found at her doorstep, or from her window, or on visits elsewhere in the islands, where she gathered notes and sketches, “like a squirrel hoarding sustenance for the winter's work in her Glasgow studio.”

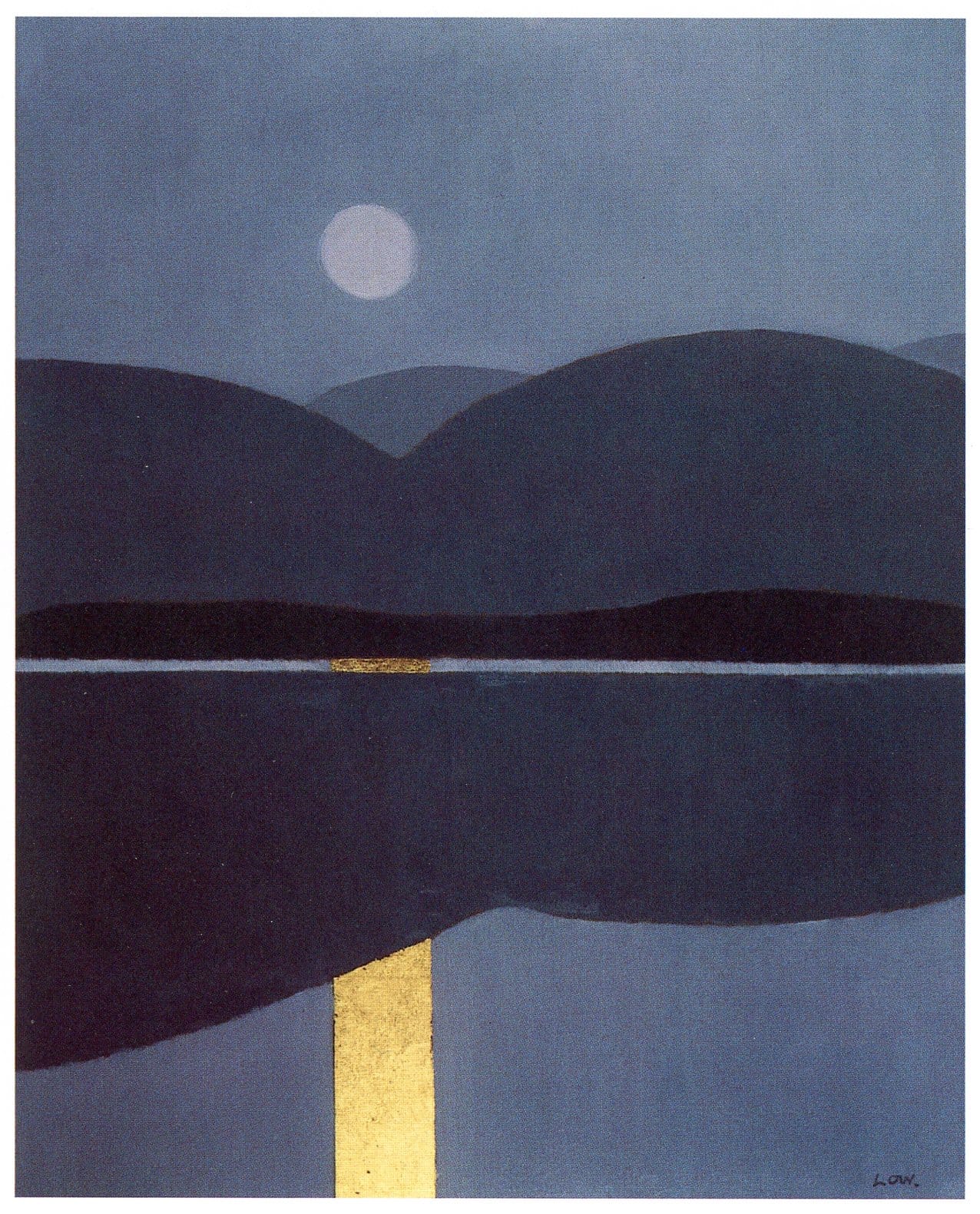

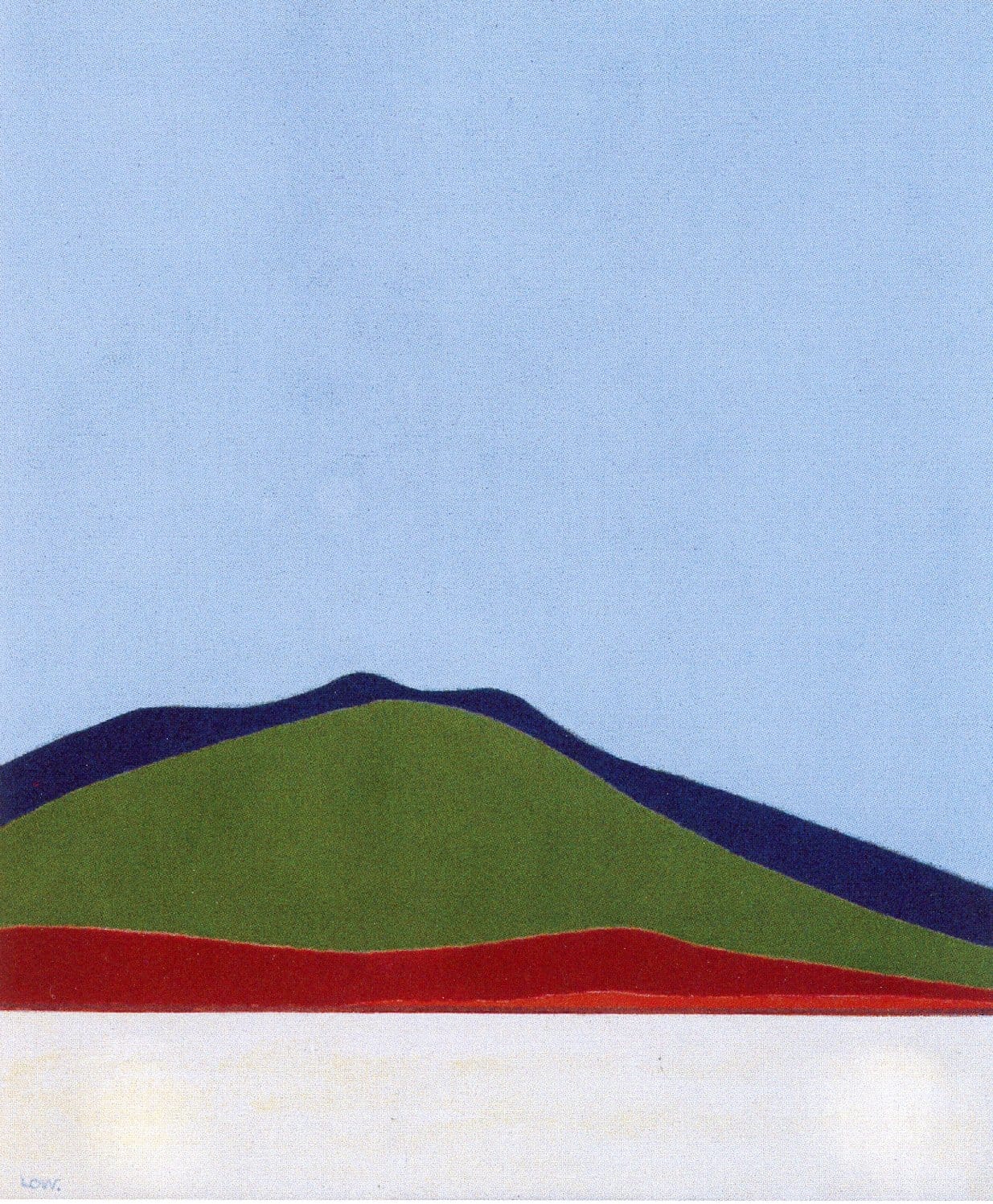

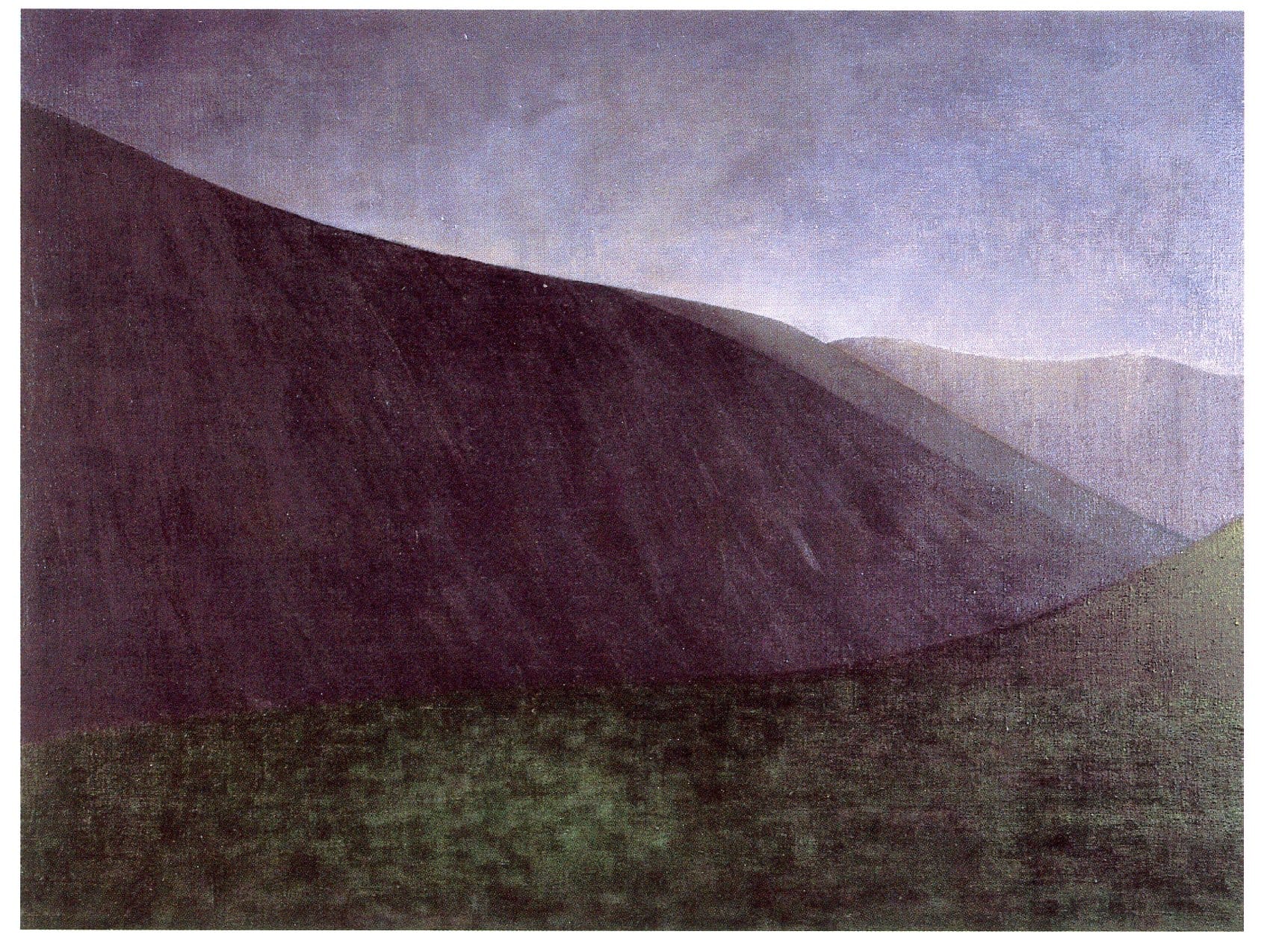

Bet Low, Red Rysa c. 1970s. Pier Arts Centre Collection. Courtesy of the Bet Low Trust.

Almost immediately captivated by the landscape, the sky and patterns of weather, Low’s work was often characterised by a responsiveness to the effects of cloud and mist, expressed through subtle deployment of tonal silhouettes. She produced “hundreds” of paintings in Orkney, as she informed the Pier, in a letter thanking the gallery for accepting her gift of three pieces, illustrated herein. Having “got so much from Orkney, it seems only fitting to try and give a little back,” she wrote in 1995. [10] It was “just a small gesture.”

Low and MacDonalds’ links with Hoy, and with Orkney more generally, thus date from around a decade later than Finlay’s briefer, though no less formatively significant visits to Rousay. Before he Sue were finally able to leave Edinburgh, in May 1965, he looked in vain for new opportunities to return to the islands. The idea – a dream, really, one among several – was quite impractical, including for financial reasons: even a wartime hut (however interesting a thought as regards a major direction taken in his work later on) would likely have been beyond their means at that stage.

That Finlay did not return at that time, or for so long afterwards, not until 2005, helps in part to account for the fact that the details of his relationship with the place locally fell out of mind. To the wider world, which of course knows more about Stonypath than Sourin (say), the rather fanciful claims he made about the history of his connection with the place became accepted fact, more or less. After all, he had a reputation as a stickler for clear definition – wasn't that what the Fulcrum Affair was all about? – and if he said he had been a shepherd in Orkney, and spent the post-war years there, then he ought to know. That this in its extended and partly private version was essentially a myth, and a creatively vital one, only testifies to the value of its claims as "truth". (Those who know their Visual Primer will know which statements I'm referring to.)[11]

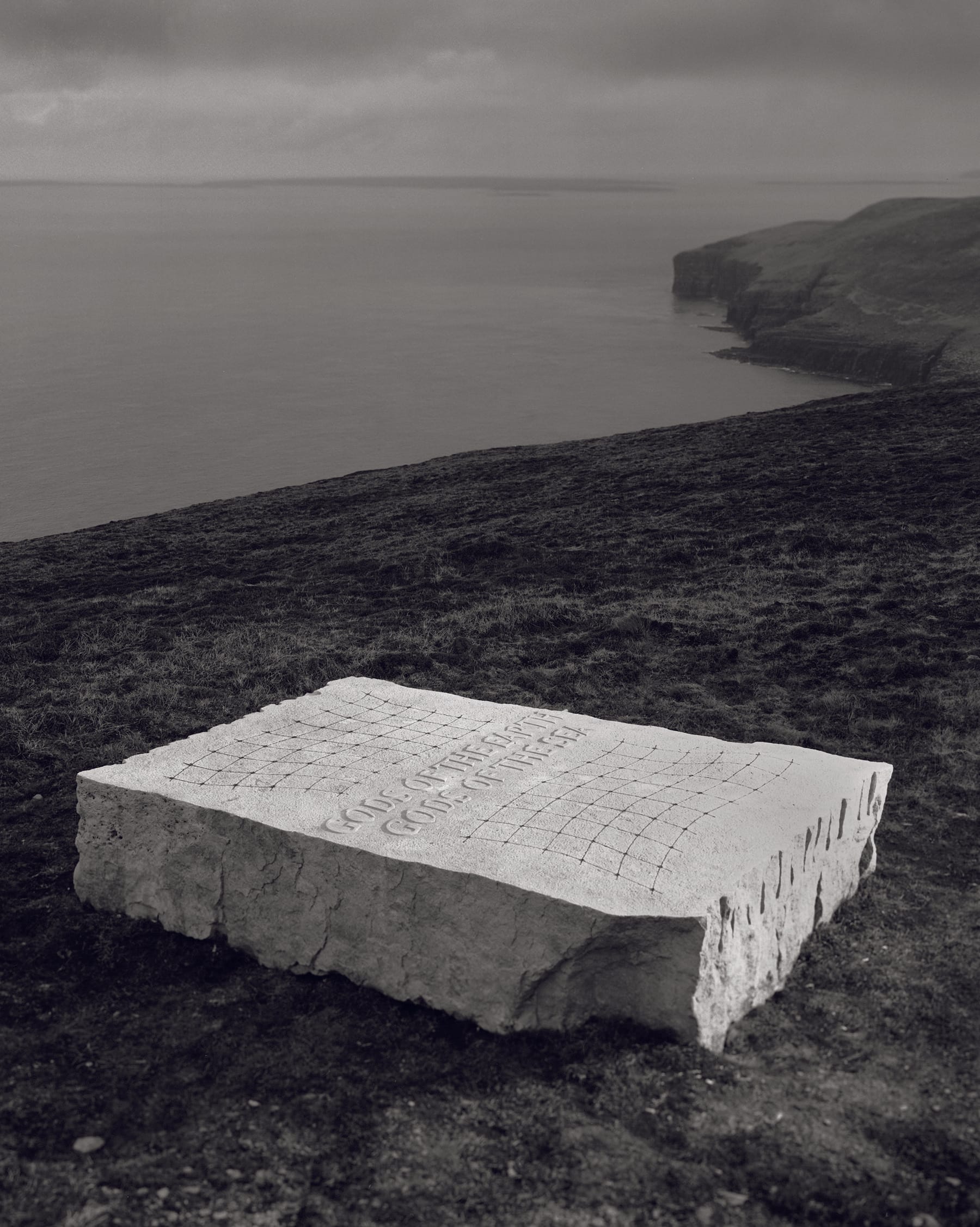

Thanks to the Pier, however, and, to an extent, as in Low’s case, to the importance the poet/ artist himself placed on the early and continuing sense of connection, it was marked in 1999 by the commissioning of Gods of the Earth/ Gods of the Sea, about which more in a later post.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Gods of the Earth/ Gods of the Sea, 2005. Photograph by Robin Gillanders, 2007. Pier Arts Centre Collection

In a further connection, the two artists' individual preferences among the islands, Hoy and Rousay, are the hilliest of the smaller islands of the archipelago, which are mostly low-lying, green and – perhaps surprisingly to anyone unfamiliar with the place – agriculturally very fertile. The contrasting untamed aspect of Hoy, wild, windswept, with huge, sea-battered cliffs, is there implicitly in Low’s work, although in general she evokes its more agreeable moods, sheltering, shimmering, enfolding, registering a “sometimes quite extraordinary fusion between the elements and of the magical quality of the light,” as Oliver wrote.[12]

Bet Low, In the Hoy Hills (Orkney) 1977. Pier Arts Centre Collection. Courtesy of the Bet Low Trust.

Comparably, Rousay’s dark mass of heathery hill-ground, evident in Gillanders’ photograph, helped it become, in Finlay’s short lyric “Poet”, his “dear black sheep”. Surreal at times, witty and idiosyncratic, touched with what the American critic Hugh Kenner termed “a bleak and casual panic”, the representation of the place in his early poems also reflects a home-like intimacy of connection, even possessiveness.[13]

These characteristics tended to encourage an assumption among many readers that Finlay was indeed an islander, an impression that he did little to discourage. Indeed in ways both straightforward and complicated, as implied above, Finlay regarded himself as in a sense having been born in Orkney, at least “as a poet”. For someone habitually in wellies (or "seaboots") and a woolly jumper it was arguably a more “appropriate” native island than New Providence.

Low seems to have been much less of a myth-maker than her old friend, but it’s tempting to wonder whether the subject of Orkney, real or imagined, arose in later years, when Low visited Finlay at his inland "island" of Stonypath, Little Sparta.

Dates and venues

Bet Low - An Island On Your Doorstep and Ian Hamilton Finlay and Orkney are on display at the Pier Arts Centre, Stromness, from 1 March until 7 June.

(A further note on Bet Low may be found on the Lyon and Turnbull website.) [14]

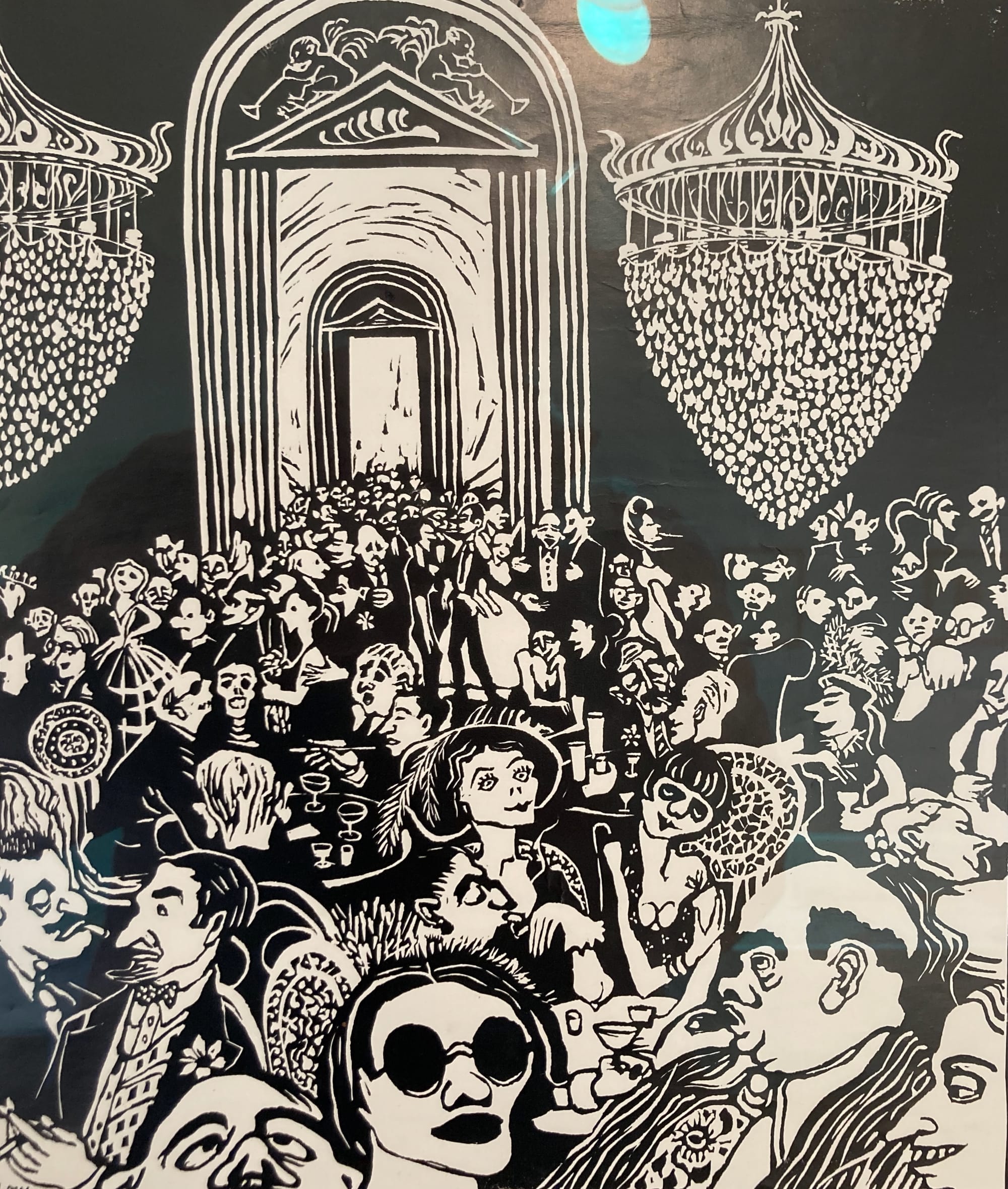

Bet Low, Festival Club Edinburgh, 1947, at the Pier Arts Centre

Ian Hamilton Finlay at Modern Two in Edinburgh opened on 8 March and will close on 26 May.

Ian Hamilton Finlay ark/ arc, at Modern Two, Edinburgh

Ingleby's Ian Hamilton Finlay: Fragments is running in Edinburgh from 3 May until 14 June.

Ian Hamilton Finlay Three Pedestals: Robespierre, Saint-Just, Couthon, 1987, with Iain Stewart, at Ingleby, Edinburgh

Lastly, Dunoon MOCA's A Centenary Tribute to Ian Hamilton Finlay is on show from 10-31 May.[15]

Subject to any last-minute changes, After Catameringue Part III, in which we return to the New Town, will appear in a fortnight or so.

https://gsaexhibitions.co.uk/exhibition/bet-low-an-island-on-your-doorstep/; https://www.flemingcollection.com/scottish_art_news/news-press/bet-low-an-island-on-your-doorstep ↩︎

Cf. Stephen Bann, "Ian Hamilton Finlay, An Imaginary Portrait", in Alec Finlay (ed.) Wood Notes Wild (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1995) p.56 (?) ↩︎

https://www.nationalgalleries.org/exhibition/ian-hamilton-finlay ↩︎

https://www.inglebygallery.com/exhibitions/7210-ian-hamilton-finlay-fragments/overview/ ↩︎

https://www.thetimes.com/uk/scotland/article/this-great-scottish-artist-was-not-an-antisemitic-fascist-d5sqz63bl (paywall); and cf, e.g., https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/mar/23/ian-hamilton-finlay-review-scottish-national-gallery-of-modern-art-two-edinburgh-centenary-show; https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/may/02/ian-hamilton-finlay-review-victoria-miro-gallery; https://www.instagram.com/p/DJW--BDtu0j/?img_index=1 ↩︎

https://gsaexhibitions.co.uk/exhibition/bet-low-an-island-on-your-doorstep/ ↩︎

Patrick Eyres “Introduction” in Patrick Eyres (ed.), New Arcadian Journal no.61/62 ([Bradford]: New Arcadian Press, 2007) p. 9. ↩︎

Cordelia Oliver, “Bet Low and Scottish Landscape”, in Bet Low: Paintings and Drawings 1945–1985 (Glasgow: Third Eye Centre, 1985), p. 10. ↩︎

Ibid. p. 5 ↩︎

Letter, 24/3/95, to Neil Firth, Director of the Pier Arts Centre. Pier Arts Centre Collection. ↩︎

See especially "I hate autobiography and biography (both), because it seems to me that much of one’s life is only nominally related to oneself, yet the telling of it seems to assume that it is telling about the person in a 'true' sort of way." Yves Abrioux, Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer (London: Reaktion, 1992) p. 159. ↩︎

Oliver (1985), p. 11. ↩︎

Abrioux (1992), p. 250. ↩︎